How to Account for Customer Incentives under IFRS

Buy one, get one free… Discounts on future purchases… Coupons for free products… Loyalty points… Sounds familiar?

Well, if you work in a company that sells some products or services to individuals or general public (not the other businesses), then you probably use some “carrots on the stick” to persuade people to buy.

Here, the question arises:

How can you account for these incentives correctly under IFRS?

I often saw that companies simply recognized the cost of these promotions as their marketing cost in profit or loss.

Yes, this is simple and easy solution, but not the correct one.

In today’s article, we will try to explain the rules guiding us in this area and I will illustrate it on examples.

What do the rules say?

In the past, the guidance was quite confusing and spread over different standards and interpretation.

For example, we had to apply IFRIC 13 Customer Loyalty Programs to accounting for loyalty awards to customers.

For other transactions, there was IAS 18 Revenue, but that standard was quite general and did not offer much guidance. As a result, there was no clear guidance on how to account for future discounts, or coupons.

Luckily, we have new IFRS 15 Revenue from Contracts with Customers now in place and the guidance is quite extensive.

However, there is no general rule on all customer incentives.

Instead, different parts of the standard will apply to different promotion tools and again, it requires careful assessment.

To give you a hint, let me name a few main points that you need to consider:

- Is the incentive provided to your customer right at the inception of the contract (i.e. is it known before purchase)?

Or, did you provide the discount, free goods or something else after the inception, while the contract is in place?In general, if it’s at the inception, then the customer incentive might be considered separate performance obligation because it’s a material right and you might need to allocate the transaction price to it.

If it’s not provided at the inception, then the customer incentive might be just a bonus to a good client and therefore no allocation of the transaction price to the performance obligation is necessary.

Instead, you might need to recognize a provision under IAS 37 (based on the character of the incentive), adjust the estimate of the transaction price or do something else.

- If you provide volume discounts, do you apply them prospectively for new purchases only?

Or, do you apply them retrospectively? In other words, does the total price for customer’s purchases depend on the total volume of goods purchased during some period?

If you apply discounts only prospectively, for new purchases only, this could be seen as a material right – a customer’s option to get additional goods at discount.

However, if you apply discounts retrospectively, this is a variable consideration in determining the transaction price.

- Do you offer prospective discounts to all customers for big bulk purchases?

Or, did you offer the specific discount to one customer only because of that specific contract?

If the discount is offered in connection with the specific contract while higher prices are charged to other customers, then you might have a material right.

If you offer the discount to all big bulk customers, then it’s not a material right. Instead, you have a variable consideration.

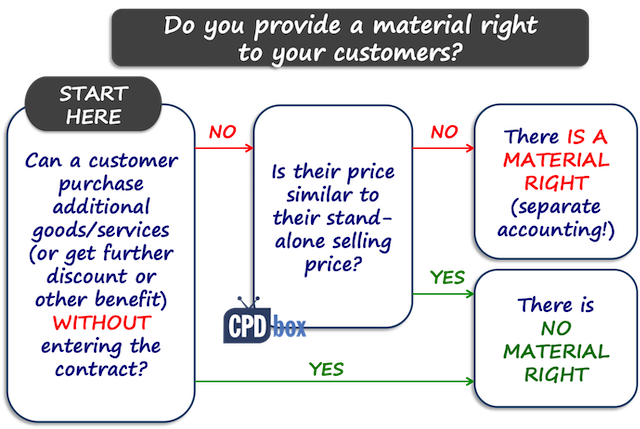

You might have well noted that “material right” shows up quite frequently. But, what is it?

What is a material right?

A material right is some benefit provided to a customer that it would NOT receive without entering into the contract.

For example, you sign a contract for network services for 1 year at CU 50 per month and the contract says that you can get 1 extra month at no cost after the 1st year.

That’s a material right, because you would NOT be able to get 1 month free without signing the network services’ contract first.

Once you identify a material right in the contract with the customer, then you MUST treat it as a separate performance obligation.

Let me tell you that many companies got it wrong – they simply forget to identify a material right, then they don’t allocate any transaction price to it and when that right is exercised, then they don’t book any revenues, just costs.

Wrong, wrong, wrong.

Before I explain this practically on a few examples, I want to show you HOW you can identify the material right.

Is there a material right?

You should answer 2 basic questions to find out whether there is or is NOT a material right:

- Can your customer get an additional good or service WITHOUT entering into another contract?

If yes, then there’s no material right, because the customer can get the goods or services anyway.

If no, then go to question n.2.

- Can the customer buy an additional good or service at the same price as the stand-alone selling price?

If yes, then there is no material right, because the customer can buy the same at the same price anyway.

If no, then yes, there is a material right and you MUST treat it as separate performance obligation.

How?

Let’s see some examples.

Example 1: Additional services at discount

Question:

ABC is a provider of network services and to boost its sales, it offers to each customer who signs up for 12-month contract one month of free service after 12- month period of paid services is over. The price of 1-month service is CU 50.

How shall ABC account for this contract under IFRS 15?

Solution:

It seems that there is a material right in this contract because the customer would not be able to get one month of free service without signing up for 12 months first.

Therefore, there are 2 performance obligations in this contract and ABC must allocate the transaction price to both of them:

- Network services

- Material right – 1-month of free service

The next step is to determine the transaction price – in this case, it is 12 x 50 = 600.

Then, ABC needs to allocate this price to both performance obligations based on their relative stand-alone selling prices.

Well, we know the stand-alone selling price of network services – it is CU 50 per month.

What about the stand-alone selling price of material right?

ABC needs to estimate the likelihood that the customer will use the additional free service (or other offered product/service in other cases). Here, let’s say everyone wants one month extra at no cost, so let’s say the probability is 100%.

Therefore, our estimate of stand-alone selling price of the material right is 100% x the discount of CU 50 (remember, the price of 1-month network service) = CU 50.

Let’s do the allocation:

| Performance obligation | Stand-alone selling price | Allocated transaction price |

|---|---|---|

| Network services | 600 | 554 |

| Material right | 50 | 46 |

| Total | 650 | 600 |

*Allocated transaction price to network services = 600/650*600 = 554, similar with material right: 50/650*600 = 46

Fine.

Now, we can recognize the revenue as services are provided. The client’s billing is CU 50 per month, but ABC can recognize only 554/12 as the revenue from network services per month – that is CU 46.

The journal entry is:

-

Debit Receivables to customers: CU 50

-

Credit Revenues from network services: CU 46.2 (554/12)

-

Credit Contract liability: CU 3.8

ABC makes the same entry each month during 12 months if nothing changes.

Then after 12 months, the revenues from network services are 554 (as shown in the above table), but there’s also a contract liability of CU 46 (3.8*12, pardon me for some rounding).

When the customer enjoys its one-month of free service, then ABC will recognize the revenue from that service as

-

Debit Contract liability: CU 46

-

Credit Revenues from network services: CU 46

The main point is that instead of recognizing the revenue from 12 month services at 50 per month and then zero for the free month, you need to recognize the revenue from both 12 months of paid service and the material right.

Now, seriously, I bet most people simply don’t care and recognize zero for free services! 🙂

Example 2: Loyalty points

Question:

DEF, the supermarket chain, issues a loyalty card. For each purchase of CU 100, the customer gets 1 point. The customer can get a discount of CU 1 per 1 point on future purchases.

During the December 20X1, customers collected 80 000 points and based on past statistics, DEF assumes that 90% of customers will use these points for future discounts.

Solution:

Here, there are also 2 performance obligations:

- Goods sold, and

- Material right – points.

The transaction price is 80 000*100 = 8 000 000, because customers collected 80 000 points for every CU 100.

The stand-alone selling prices of goods is the same as the transaction price – CU 8 000 000.

What about the points?

DEF expects 90%*80 000 points to be redeemed, so their stand-alone selling price is 72 000 (80 000*90%; that is 0,9 per point).

Let’s perform the allocation:

| Performance obligation | Stand-alone selling price | Allocated transaction price |

|---|---|---|

| Goods | 8 000 000 | 7 928 642 |

| Material right | 72 000 | 71 358 |

| Total | 8 072 000 | 8 000 000 |

So, DEF recognizes the revenue for the goods sold as follows:

-

Debit Cash: CU 8 000 000

-

Credit Revenues from goods sold: CU 7 928 642

-

Credit Contract liability: CU 71 358

And, when the points are redeemed, then DEF can recognize the revenue from the points:

-

Debit Contract liability: CU 71 358

-

Credit Revenues from goods sold: CU 71 358

Yes, it can happen that the customers redeem more than 90%. In this case, the revenues are recognized only up to the amount of contract liability and DEF should probably reflect this fact in new estimates for new points.

If customers redeem less than 90%, then the remaining contract liability is recognized in revenues when the points lapse.

Example 3: Buy one, get one free

I have already described it in one of my previous article together with the example, so please check it our here.

Finally…

Maybe you ask yourself:

Why should we really account for that material right separately? It’s a lot of work and hassle, and everything ends up in revenues anyway.

Well, that’s true, but the timing of revenues is important.

Let’s take example n. 2 from above.

By showing the material right separately, the readers of your financial statements know that at the end of 20X1, you have some liability there – to provide discounts on future purchases resulting from loyalty points.

If you don’t show this separately, then you are effectively hiding your liabilities and overstating your revenues.

Do you also provide some treats to your customers to get some sales? And, how do you account for them? Please, leave me a comment below!

JOIN OUR FREE NEWSLETTER AND GET

report "Top 7 IFRS Mistakes" + free IFRS mini-course

Please check your inbox to confirm your subscription.

48 Comments

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Recent Comments

- mahima on IAS 23 Borrowing Costs Explained (2025) + Free Checklist & Video

- Albert on Accounting for gain or loss on sale of shares classified at FVOCI

- Chris Kechagias on IFRS S1: What, How, Where, How much it costs

- atik on How to calculate deferred tax with step-by-step example (IAS 12)

- Stan on IFRS 9 Hedge accounting example: why and how to do it

Categories

- Accounting Policies and Estimates (14)

- Consolidation and Groups (25)

- Current Assets (21)

- Financial Instruments (56)

- Financial Statements (54)

- Foreign Currency (9)

- IFRS Videos (74)

- Insurance (3)

- Most popular (7)

- Non-current Assets (56)

- Other Topics (15)

- Provisions and Other Liabilities (46)

- Revenue Recognition (27)

- Uncategorized (1)

Hi Silvia, thanks for this interesting article and wonderful cases.

In terms of the loyalty points redemption in second case, I have one question: if there are more points redeemed than estimated, let’s say 80,000 points instead of 72,000 are redeemed, becuase in the article you wrote that we cannot recognise extra revenue (only up to the contract liability amount), so what journal will be for these some extra 8,000? should it be Dr. Cost of goods sold and Cr. contract liability? many thanks.

Hi, we are in pharma industry where if customers buy 5 products ( Products price 1 products=CU100 then we offer 1 extra products for bonus. please give the journal entry of sales with COGS entry.

Hi Sylvia, How would the Trade in’s be treated under IFRS 15, Our company sold Software licenses and customer’s bought renewal agreements in order to gain customer service access and download free upgrades each year. Last year our company decided to stop selling licenses and agreements and moved to subscription Sales. Now the company is running promotions to get customers who lost the right to buy renewal agreements to buy subscriptions at a discounted rate. Would this be considered as a Trade in of old licenses to gain latest software? and how would the accounting of this look?

Great Silvia, your explanations are real life and easy to grasp. Your pack is really loaded for professional examination for office and home students’ successes on financial reporting.

Hi Silvia,

Thank you for the great website. In regards to cash back rewards based on the amount the customer spends on their credit card, how would these rewards be calculated? As a payment fintech the revenue is derived from the interchange from customer purchases. Customer receive 1% cash back on their spending through the credit card (product). Currently, the points do not expire or have a limit. Any guidance or insight would be much appreciated.

Hi Sylvia,

Appreciation if you could advice me on this issue, My Company has loyalty programme whereby customer could earn reward point by giving product review. May I know how to determine the value of that reward point as there is no purchase value.

Thanks

Hi Peyton,

this is too little information to give the advice to you. If there is no purchase value, then what is the benefit of these reward points for the customer? This is the point. You need to attribute certain value to the benefits granted to customers (or in other words, performance obligations) and then decide on the accounting treatment based on the moment of satisfying that performance obligation. S.

My company is putting a place a similar program , clients will get points for joint marketing initiatives and these points can be redeemed aa discounts to future purchases. In this, not knowing what the future purchase might be, how do we account for it? If the points instead equate to dollar value vs % discounts this is easier. In this would you create a contract liability for the material right and then allocate this to the performance obligation once a new purchase is made? On the other if a % discount very difficult to allocate any dollar value not knowing what the future purchase will be. Any advice?

The reward point earned by writing review can be used in next purchase. Eg Mr A earned $10 for writing review and it can be used in future purchase.

Sorry, i’m not very clear about how to calculate the attribution of value since they is no purchase value?

@ Silvia,

Hope to get your feedback on this.

Thanks in advance.

When selling items, we earn loyalty points with a face value and we set it as a deferred revenue against teh sales revenue. This will be recognized based on a rate as we go alone. But when redeeming the points that the customer has acquired, . i.e. use points in lieu of cash payment, what is the accounting entries for it?

How do we account for instances when we our website is used to market 3rd party product and we get paid a referral fee.

Thank you for a great website? What guidance / steps are appropriate / best in deciding on whether a credit card loyalty programme is inside or outside the scope of IFRS 15? e.g. should a portion of the interchange fee be deferred until rewards are redeemed or should the full interchange fee be recognised as an income, with a provision for the rewards payable to customers when they exercise their rights?

Amazing, now I understand IFRS 15 which I need for my CPA exam.

Hi Sylvia,

Thanks for this brief summary!

I have a question — we have a pre-existing contract with a Hotel Operator (us being the owner of the asset being managed by this operator) that is expiring 1 year from now. The operator sought to extend it to another 20 years and as a result they are offering us c. 30M to incentivize us to commit on the extended contract. This 30M is a free cash and can be used by us in any ways (i.e. no liens or encumbrances). How do we account for the 30M compensation?

Wonderfully explained

Hello Silvia!

Your question in this article, “Do you also provide some treats to your customers to get some sales? And, how do you account for them? Please, leave me a comment below!”

My answer is as this is a cost to obtain the sale and therefore need to be adjusted against transaction price and revenue to be shown net of it.

hello silvia, What about the cash back offer? For example, if an application offers cash back when payment is made from such application, what will be the treatment of such offer?

Will it be treated as reduction in revenue?

Thanks for a very interesting and informative example. What would happen in the case where a discount is offered indefinitely on future purchase of related goods?

For example – if we sold tools for CU 50,000 and as part of this sale offer discounted (consumable) blades (which can only be used with these tools) for CU 20 each (normal price CU 40). Estimated usage of the blades is around 1,000 units per year, but the discount would be offered indefinitely. What would be the accounting treatment please? It sounds as if there is a material right, but how would one value it?

Kind regards

Great example. In loyalty points example, what if the redemption rate is higher than the estimation. Say the it turns out 95% of the points were used, how should the extra 5% should be recorded?

What if the company is recognizing the revenue in cash basis. Instead of accrual basis.

Eg.

While raising an invoice of Rs. 120000 the client is given a discount of Rs. 20000 and Rs. 100000 is paid by the client in two different financial period Rs. 50000 thousand each.

Now, for this cash payment made by the client he is awarded 5000 points of Rs. 1 each point.

While raising another invoice of Rs. 10000 the client has redeemed 5000 points. The final invoice less redeemed point of Rs. 5000, the client has paid Rs. 5000. In the books, the company is recognizing this Rs. 5000 as revenue.

How we need to treat loyalty points liability in such case where the revenue is recognized on collection basis??

Dear Silvia

Thank you for providing such deep insights regarding “How to account for customer incentives under IFRS 15”. I am still not clear about certain aspects of customer incentive such as

i) Wholesale company provides free insurance coverage to their dealers if they purchase a specified amount of products during the financial year. How should this transaction be treated as a reduction of revenue or marketing expense? In addition, it may be mentioned here that insurance plan is purchased by the company from insurance company so that they can provide it to dealers.

II) Retail company provides free foreign tour to their customers if they purchase a specified amount of products during the financial year. How should this transaction be treated as a reduction of revenue or marketing expense? In addition, it may be mentioned here that foreign travel tour plan is purchased by the company from travel agency so that they can provide it to customers.

Thanks in advance. Appreciate your effort and time to make IFRS easy for everyone..

Warm regards

Mymoon

hi have same doubt as mymoon point no.2 please help to advice.

Great Content. How do you come up with the figure of 7 928 642 in the second example, Can you please explain. Thanks

(8 000 000/8 072 000)*8 000 000

Dear Silvia,

is accrual for loyalty programs a subject of IFRS 9? Is it a financial instrument?

Many thanks,

Dagmara

No, it’s not IFRS 9 as it does not meet a definition of financial instrument.

Hi Silvia,

Great stuff!! I have a doubt with regard to accounting of rewards program as mentioned below:

If an exchange house is issuing reward cards (free of charge) to it’s all customers (new and existing customers), and upon doing the first transaction with Exchange house it is crediting 5 initial points to the issued reward card balance. After first transaction, each subsequent transaction will give 2 points to the customer. And when customer accumulates 10 points, customer can redeem same equivalent 10 USD. If the company is recognizing the expense only when customer actually redeeming the balance, will that amount to a wrong accounting practice? According to me there is a ‘material right’ when customer finishes first transaction and performance obligation got created. Am I correct in this and how to recognize the unredeemed reward points? Transaction fee and commission are the general revenues for the remittance transactions of exchange house.

Many thanks

Dear Silvia,

Thank you for the great content! You are a source of inspiration and knowledge!

I have a question in relation with Example 2. As you say “it can happen that the customers redeem more than 90%. In this case, the revenues are recognized only up to the amount of contract liability and DEF should probably reflect this fact in new estimates for new points.

How do we account for the excess points claimed?

Thank you and kind regards.

Hi Milena. If the customers redeem more than 90% of points as expected, the cost of goods sold will be larger than expected. So refer to example 2, lets say the customers redeem the points by buying products of $1 each. We first expect customers to redeem 72,000 points so we expect they buy 72,000 goods of $1 each. Then if the customers redeem all 80,000 points in reality, they will buy 80,000 goods of $1 each. As a result, we use up 8,000 more goods for the customers to redeem. This will be reflected in a larger cost of goods sold figure in our income statement. Overall, we will have an accounting mismatch due to larger cost of goods sold (80,000 goods consumed instead of 72,000 goods consumed) now compared to the revenue we allocated for the redemption points (72,000 points expected to be used in this case). So next financial year we may need to adjust the estimation that customers will redeem 100% of the points of 80,000 points to give a fairer view of revenue and cost of goods sold.

Great work Sylvia

Would appreciate some light on the following scenario

A supplier gives me as a part of a past contract settlement a ‘voucher’ worth CU 1000 which I can use for future purchases of a capital assets valid for 1 year(They sell Capex items only)

The questions are

– as of the signing date of the settlement contract , can I treat this as a ‘receivable’ ( A financial instrument, like a currency I can use to settle the liability when it arises later to the same supplier)

What would be the journal?

– Or does this right materialize only when I have purchased some capex items from them and these come in as a discount ?

Hi Pradeep, that would be the second case because if you can use it for future purchases it means that you cannot use it without the future purchase for anything else – thus it will become your discount at the time of purchase. S.

Thank you for your blog which is really interesting and instructive.

I was wondering what would happen if the discounts points had no expiry date, would the revenue be recognized at one moment? Or would the liability (and the revenue) stay for ever on the balance sheet?

Hi Marc, you would still have to make your estimates, based on probabilities, average time of redemption, etc. and of course, make updates of these estimates under IAS 8.

how the client would account for free goods/service will be received from the entity?

Debit zero

Credit zero

Wonderful explanation. Thank you

Hi Silvia

The way you explain is amazing. Super. Really your articles help me a lot.

Thanks

Rgds

Well explained and I would like to have more examples

relating to capitalized contract costs.in particular ,the period over which they should be amortized.

THANKS FOR YOUR EFFORTS.

hello silivia, thanx for the article its really helpful, now am confused, you have at first recognized a contract liability of 46 then continued to say after the one free month you Dr. contract liability and recognized now revenue by credit the revenue account.

now my question is??

lets say the customers stops to use the services after the 12 month period, do u still Dr. contract liability? if yes, am pluzzled is there a time when that contract liability becomes payable? now if its a No for this, then whats the need for recognizing it as such

Hi Edmund,

thanks a lot for your question!

After 12 months, when the customers stop using the services and at the same time, the incentives lapse, you need to recognize revenue: Debit Contract Liability, Credit Revenue. I think it’s written also above in the article. S.

Thanks a lot

Wonderfully explained

Excellent Answer¡¡

Wonderfully explained and the examples properly simplified. Well done.

Great content!

Amazing effort